Megatrends are powerful, disruptive forces that shape economies, businesses and societies. They drive innovation, steer investment and create new ideas. Identifying these trends helps guide us to opportunities – and away from risks. They steer us towards those sectors and industries with a clear runway of growth, enabling us to build better, future-proof investment portfolios.

In this series of op-eds Rob Clarry, Investment Strategist at wealth manager Evelyn Partners, will identify four big themes that could reshape global economies and markets in the long and very long terms.

Clarry says: ‘We’re at an inflection point today. The relative macroeconomic stability of the Great Moderation – which spanned the past four decades from 1980 to 2020 – is over and the years ahead are set to look very different.

‘We see four megatrends as shaping the next decade and beyond: shifting demographics, changing world order, energy transition, and technological revolution.’

Here he addresses the first of these with the other three to follow in subsequent weeks.

HOW AGEING POPULATIONS AND DEMOGRAPHIC SHIFTS COULD SHAPE GLOBAL INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES

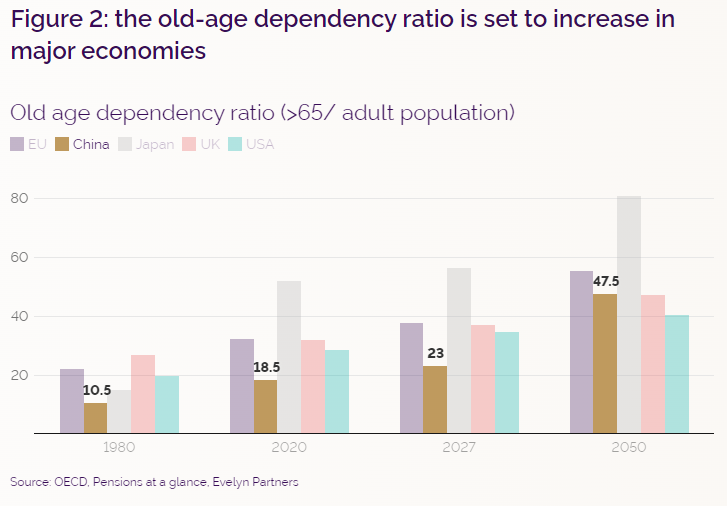

The developed world is ageing. In 2050, there will be 80 pensioners in Japan for every 100 adults of working age. In contrast, parts of the emerging world are still experiencing rapid population growth. How can investors benefit from these shifting demographics?

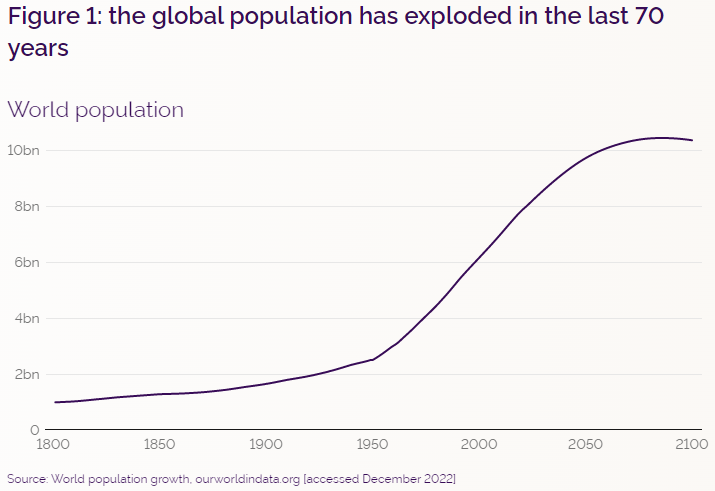

In 2022, the world population reached 8 billion with 40% growth in the last 40 years alone. This rising population is partly due to people living longer, with the number of people aged 65 and over increasing by 623 million in the past two decades alone. By 2040, this older population is set to reach 1.3 billion. Yet the global fertility rate has halved since the 1950s.

These demographic trends have proved persistent in the face of a pandemic, the obesity crisis and the ongoing struggle to find cures for killer diseases such as cancer and diabetes.

If anything, they are speeding up:

· The increase in the number of over 65s seen in the last 20 years matches that of the previous seven decades [1]

· Life expectancies have risen from a global average of 49 years in 1955 to 72 years today, a 47% increase

· The pandemic led to a ‘baby bust’ in many countries, with the UK experiencing its lowest-ever fertility rate in 2020 [2]

Several emerging markets are facing ageing populations too

While ageing populations have been thought of as a developed market phenomenon, by 2050 two-thirds of the world’s elderly will live in emerging markets[3]. One of the most significant demographic timebombs is in China, where the one-child policy has left an ageing population dependent on fewer and fewer working people. This is labelled the 4-2-1 problem, where a single child cares for two parents and four grandparents.

In many ways, ageing populations are to be welcomed: they reflect improvement in nutrition, medical advances, sanitation and education. An ageing population is a proxy for human progress. However, it also brings significant challenges for governments and economies, particularly as falling birth rates reduce the labour force of tomorrow. This puts a strain on revenues and spending. It also brings about shifts in consumption patterns, with profound implications for investors.

The chart below shows that the old-age dependency ratio (the number of over 65s relative to the number of adults of working age) is set to increase across the world’s major economies over the next five years to 2027, and then sharply in the years to 2050. It is Japan that faces the biggest challenge. In 2050, there will be 80 pensioners in Japan for every 100 adults of working age.

This brings a number of important questions:

· How will their economy function with no workers?

· Who’s going to pay for pensions and healthcare?

· Who’s going to care and support the elderly people that need help?

Ageing populations are not the only demographic trend to watch

· Urbanisation has been an important phenomenon, with implications for the way people work, live and consume. Until 2009, more people lived in rural than in urban areas. This has flipped in the decade since, with 55% of the world’s population now living in towns and cities[4]. China, India and Nigeria are particular hotspots for urbanisation.

· Internal and international migration is also important. It has always been a feature of human progress, with people moving to find new opportunities. More recently, climate change and war have also pushed more people away from their homes. The number of forcibly displaced people was over 70 million in 2018, including close to 26 million refugees. This is a persistent problem for governments – few have found politically acceptable ways to deal with mass immigration.

· Global fertility rates are declining rapidly, which presents a major problem for economic growth. Put simply. economic output in a given economy is a function of labour and productivity. Setting aside productivity, the implications of falling births are quite straightforward: fewer people, means fewer workers, which means lower economic output.

What challenges do demographic trends create for governments?

Governments must wrestle with rising pension and healthcare costs.

Strain on healthcare

Although the average man in the UK can now expect to live to almost 80, his average healthy life expectancy is only 63 years [5]– he will spend 17 years with some form of health condition, such as high blood pressure, type II diabetes or heart disease[6]. This puts a considerable strain on government finances, only partially compensated by lower spending on areas such as education. As more people spend a longer time in ‘not good’ health, this will create undesirable economic outcomes: people may not be able to work, for example, or may need to fund expensive and ongoing medical care themselves.

Ageing populations mean fewer taxpayers

At the same time as costs are growing, a larger retired population leads to fewer people in work paying taxes. This holds back GDP growth and productivity. The ageing of the workforce may also depress investment[7]. Countries with ageing populations face the prospect of shrinking economies.

Governments are visibly struggling with the implications of this difficult balance. Taxes may need to rise on a shrinking working population to pay for the needs of an ageing population. The alternative is for governments to run significant deficits to support public spending. However, both options are politically uncomfortable.

Urbanisation requires new infrastructure

Governments need to ensure that there is the requisite infrastructure to support the incoming population, including adequate housing, infrastructure and education.

China, for example, has experienced unprecedented rates of urbanisation. Between 1978 and 2018, its urban population increased from 170 million to 837 million[8]. Given China’s GDP growth, its accelerated approach has been largely considered a success, though there have been challenges.

· The growth in basic infrastructure and services in urban areas has not kept up with urban population growth, impacting workforce quality and efficiency

· Coal has powered rapid growth in the manufacturing sector, which has had a hugely negative impact on the environment

· Local government debt has been pushed to unsustainable levels, which has worsened due to the recent housing market slump [9]

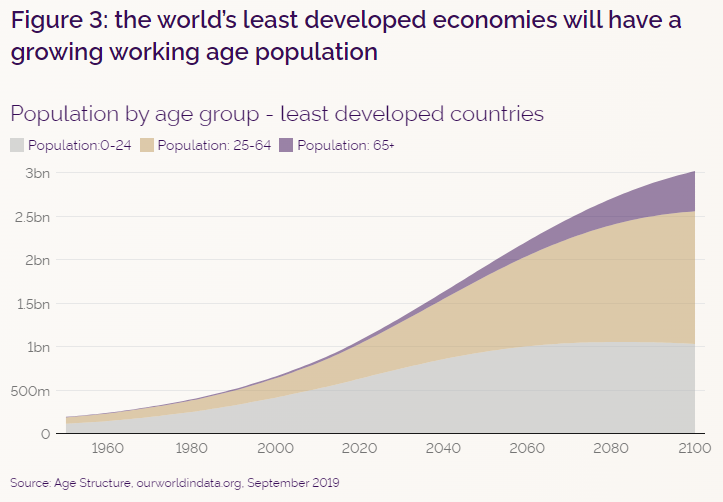

The balance of global economic power

Demographics can also change the balance of global economic power. Countries with ageing populations are likely to become less wealthy over time, while other countries will rise up. By the end of this century, the United Nations projects that Africa, which had less than one-tenth of the world’s population in 1950, will be home to 3.9 billion people, or 40% of humanity. This has long-term geopolitical and environmental consequences.[10].

Investment implications

Despite the risks presented by shifting demographics, there are opportunities for long-term investors.

Healthcare sector

A greater number of over-65s will bring age-related diseases that need to be treated – dementia, cancer, high blood pressure, arthritis or cardiovascular disease. There is also likely to be an increased focus on medical research that can address diseases that have proved difficult to treat – Alzheimer’s, for example. The OECD has said global healthcare spending is likely to outpace GDP through to 2030, reaching 10.2% of GDP from 8.8% in 2018[11]

There will be other notable trends in healthcare expenditure. For example, recent analysis from institutional investor PGIM found that by 2070, real (inflation adjusted) annual spending on nursing homes will be $325 billion greater than it is today. They also estimate that spending on medicine and drugs will climb by more than $40 billion annually over the next 50 years due to the ageing of the US population.[12]

Financial services

This is another potential beneficiary of ageing populations. As people live longer, they are likely to find cash-strapped governments less willing to support them in old age. That means they will need to save up to support themselves. According to research from McKinsey & Company, just 11% of investable assets in the US will be held by people younger than 45 by the end of this decade.

Not only does this create a significant tailwind for various parts of the financial services industry – investment management, platforms or pension providers – it may also influence the performance of financial markets themselves. As large demographic cohorts move towards retirement, it may change the demand for government bonds, or income-generative equities. While any adjustments are likely to be gradual, it can influence the price of assets at the margin[13].

Countries with favourable demographics

India, Africa and East Asia all have favourable demographics, with young, fast-growing populations. This is a tailwind for economic growth. Companies that are exposed to these regions – such as consumer goods companies – should have a natural advantage. As such, this can be a fertile area to look for opportunities. [14]

Demographics are not deterministic. However, they will influence broad consumption patterns, the outlook for government spending, and provide support for specific sectors. As investors, we need to recognise the opportunities and risks shifting demographics can create.