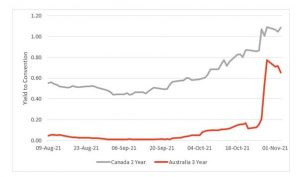

In some countries, central banks have actually started to reverse policy with the first being the Bank of Canada which recently announced the end of Quantitative Easing (QE) outright, which began November 1 2021. It also moved rate hikes closer, with April 2022 now showing up as the expected date of a first increase. In response, the Canada 2-year yield spiked by 21 basis points, to 1.08%, having more than doubled over the past four weeks. Elsewhere, the Reserve Bank of Australia has ended its policy of yield curve control, becoming one of the first large central banks to act against a post-pandemic surge in prices saying that it would no longer try to keep the yield on three-year bonds at 0.1 per cent, following a week of turmoil in short-term bond markets during which yields soared after the RBA declined to defend its cap. In the US, the Federal Reserve have announced that it will begin to reduce its massive $120bn a month quantitative easing programme by $15bn a month and Jerome Powell admitted that inflation is “running well above our 2% longer run goal”.

The central banks are, however, walking a tightrope. Given the huge amount of leverage in the system, they know that even a small rise in interest rates runs the danger of tipping the global economy back into recession. In addition, it is very hard to see how they can aggressively reverse the course of current monetary policy, with nearly all asset markets at very elevated levels. Note that the Federal Reserve is not tightening but merely expanding its balance sheet at a slower pace despite inflation running above 5%. Meanwhile, the Bank of England also recently voted to leave interest rates unchanged and continue with their current level of quantitative easing despite their own economist’s forecast of 5% inflation in 2022. European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde said the European Central Bank is very unlikely to raise interest rates next year as inflation remains too low. They seem inclined to let inflation run hot rather than tighten too soon and this obviously leads to the risk of them being behind the curve and letting inflation spiral out of control.

Hope for the best, plan for the worst

Whilst we have no idea whether the current level of inflation will be sustained or transitory, we do know that current monetary and fiscal policy settings have historically been associated with rising consumer prices and therefore know it is a scenario that cannot be ruled out. We also know that an enduring period of inflation is not being priced into most asset classes. As the title of this piece suggests, we should hope for the best, but plan for the worst. Even if we believe that the chances of a sustained rise in inflation are low, we should consider the consequences of being wrong and these look significant to us given the elevated levels of asset prices.

This was a theme explored in a recent research paper by James Montier at GMO in which he looked at which asset classes were the best store of value in the inflationary seventies. Whilst Montier himself doesn’t think that inflation is likely to be sustained he maintains that investors need to build portfolios that are robust against a range of outcomes because, like us, he acknowledges that it is always possible he could be wrong.

‘We have often talked about the need to build robust portfolios – that is portfolios that can survive multiple outcomes. This desire stems from Elroy Dimson’s excellent definition of risk as “more things can happen than will happen”. So, thinking through how to ‘inflation-proof’ a portfolio is always a worthwhile endeavour, even in the absence of a strong inflationary view.’

The paper finds that some of the asset classes which investors consider inflation hedges, such as Treasury Inflation Protected Securities or Commodities can be useful short-term inflation hedges but are less effective at preserving wealth in the long term. Conversely, asset classes such as equities can be a poor short-term hedge as demonstrated by the draw down in the early seventies but can still be a good store of value in the long term.

‘Our best recommendation is to buy true, real assets as a store of value. Foremost amongst these assets is obviously equities. They may make a terrible inflation hedge (as they did during the early 1970s), but over the long term they represent the businesses that charge prices and pay wages, so their cash flows should be real if these two elements are roughly matched. As such, they act as a store of value in the longer term.’

Within equities, however, the paper finds that holding value stocks is an even better strategy as the chart below demonstrates.

![[uns] house of commons, parliament](https://ifamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/wordpress-popular-posts/788182-featured-300x200.webp)