Fiscal relaxation

Attitudes towards fiscal support are evolving. German Finance Minister Christian Lindner is now advocating for increased defence spending representing 2.7 percent of the country’s GDP, with possible increases thereafter. A more constructive tone from Germany, long a fiscal hawk, could suggest the outcome of the EU’s review of fiscal policy, a key topic under discussion this year, may allow governments to run budget deficits at an adequate level as opposed to the straightjacket of fiscal rectitude. A more relaxed fiscal stance could underpin growth.

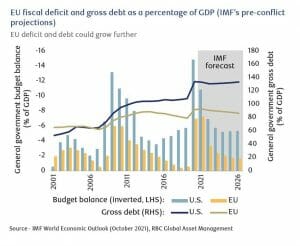

Lascelles notes there is scope for this approach, as fiscal deficits and public debt in Europe are relatively smaller than those in the U.S.

Spending will take many forms. The EU and its member states are looking to protect lower-income households and vulnerable small and medium-sized enterprises from soaring energy prices. We already saw some measures taken last autumn when prices started to spike. But as prices will more than likely remain elevated for some time, national governments, such as France and Germany, are looking to subsidise energy costs or remove gas taxes temporarily. So far, such measures amount to under one percent of member state GDPs.

Spending on energy infrastructure, such as the two German LNG terminals, is another key area of expenditure. Germany’s pledge to meet NATO’s target for defence spending of two percent of GDP led other member countries to announce similar long-term commitments, though not all will be able to follow suit given other spending requirements.

EU-wide defence spending is needed to fill capability gaps so as to improve military readiness, according to the Centre for European Reform, a think tank that focuses on European integration. At an informal summit in Versailles on March 10–11, EU heads of state agreed to a “substantial” increase in defence spending.

The debate has started as to how this will be financed. At the summit, EU national leaders agreed on the priorities of defence, energy, and economic resilience and discussed a spending programme of up to €2 trillion.

Macron put forward the idea of more joint EU borrowing. There was a general recognition that the €750 billion recovery fund to help member countries weather the pandemic had been productive by providing fiscal flexibility, enabling the EU to coordinate loans and transfers, and allowing for the issuance of debt at the EU level. In effect, the recovery fund was seen as a prototype for the response to the current crisis.

The discussion is evolving towards whether there is scope to use the recovery fund to underpin new initiatives as not all funds have been released—some member states perceive this option as more prudent. Over time, more joint debt issuance is likely, in our view. We think the probable re-election of Macron in April, as expected by a wide array of pollsters, could speed up this process.

The summit launched a dynamic framework for the March meeting of the EU Council and the forthcoming gathering in June where more details will be discussed.